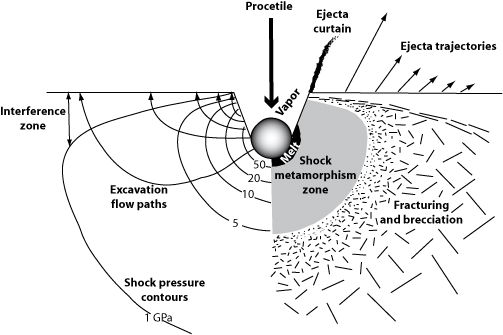

According to new research, the flaming space rock that slammed into Earth and wiped out the dinosaurs struck at the worst possible angle (for the dinosaurs, that is). Under any circumstances, colliding with a massive, fast-moving cosmic projectile would have been disastrous. Researchers recently discovered that this massive space rock also struck the planet at a steep angle, resulting in the “deadliest possible” outcome by releasing far more gas and pulverized rock than it would have with a shallower approach. Scientists created the first 3D simulations of the asteroid’s path as it hurtled toward Earth, tracing the event from beginning to end: from the asteroid’s approach to the crash to the formation of the giant crater in its entirety. According to the study, the asteroid approached its target from the northeast and struck at an angle of about 60 degrees above the horizon, maximizing the amount of gas spewed into the atmosphere — with catastrophic results for global climate.

It happened around 66 million years ago, and it marked the end of the Mesozoic era. The event caused global climate change and mass extinction, eliminating 75% of all life on Earth, including all non-avian dinosaurs. The Chicxulub crater, a massive circular basin beneath Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula measuring around 124 miles (200 kilometers) wide, is still a scar from the impact.

In the researchers’ simulations, they modeled an asteroid measuring about 11 miles (17 km) in diameter, traveling at approximately 27,000 mph (43,000 km/h) and with a density of 164 lbs. per cubic foot (2,630 kilograms per cubic meter).

Take an object the size and mass of this ancient asteroid and send it hurtling toward Earth at tens of thousands of miles per hour at an angle 60 degrees above the horizon, and it would have blasted a crater that closely matches the structure of the Chicxulub crater, according to the simulations.

The ejecta from such an impact would have produced “the worst-case scenario” for the planet, according to the models, spewing up to three times as much sulfur and carbon dioxide into the atmosphere as other impact angles did.

According to lead study author Gareth Collins, a professor of planetary science in Imperial College London’s Department of Earth Science and Engineering, this steep-angled trajectory “was among the worst-case scenarios for the lethality on impact.”

“It put more hazardous debris into the upper atmosphere and scattered it everywhere — the very thing that led to a nuclear winter,” Collins said.